What Is Just Facts About Immigration Review of Website

The United States has been shaped by successive waves of immigration from the arrival of the first colonists through the present day. Immigration has wide-ranging impacts on society and culture, and its economic furnishings are no less substantial. By irresolute population levels and population growth, clearing augments both supply and demand in the economy. Immigrants are more likely to piece of work (and to exist working-age); they likewise tend to hold different occupations and educational degrees than natives. By the 2nd generation (the native-built-in children of immigrants), though, the economic outcomes of immigrant communities exhibit hit convergence toward those of native communities.[ane]

This document provides a set up of economic facts about the role of clearing in the U.Southward. economy. It updates a document from The Hamilton Project on the aforementioned subject area (Greenstone and Looney 2010), while introducing additional information and research. We describe the patterns of recent immigration (levels, legal status, country of origin, and U.Southward. country of residence), the characteristics of immigrants (education, occupations, and employment), and the furnishings of clearing on the economy (economic output, wages, innovation, fiscal resources, and crime).

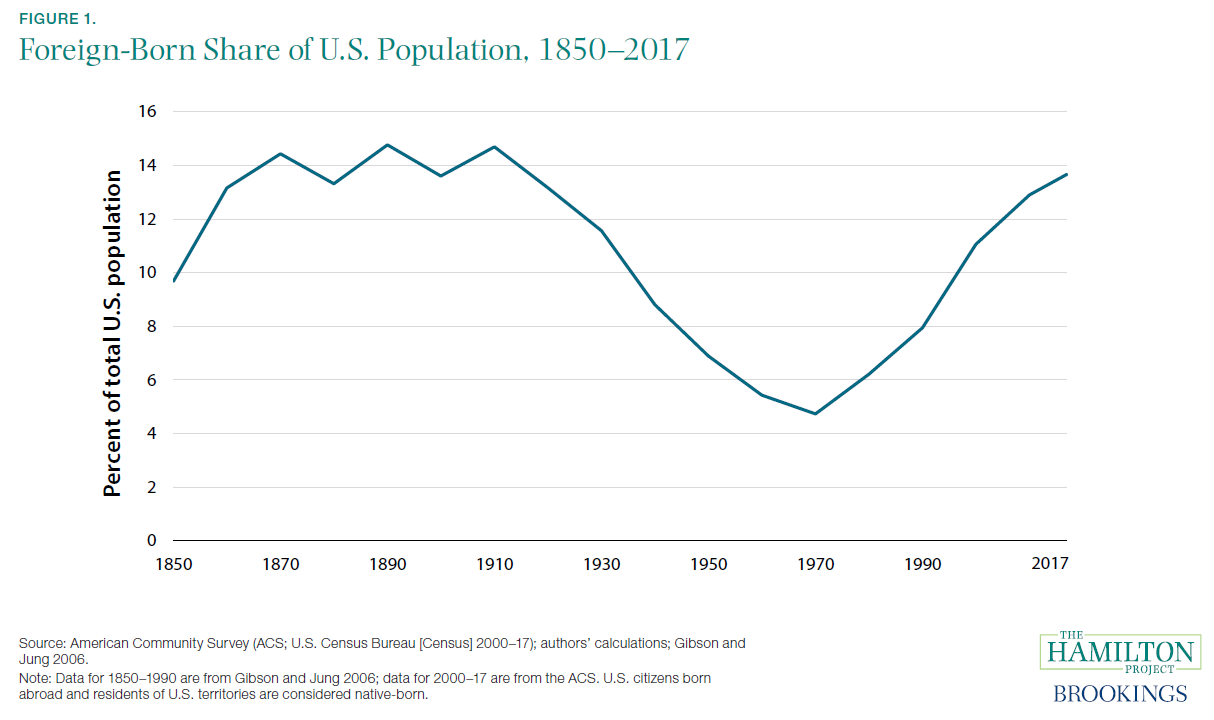

In 2017 immigrants made up nigh 14 percent of the U.South. population, a sharp increment from historically depression rates of the 1960s and 1970s, but a level usually reached in the 19th century. Given native-born Americans' relatively low birth rates, immigrants and their children now provide essentially all the net prime number-age population growth in the United states of america.

These basic facts propose that immigrants are taking on a larger role in the U.Due south. economic system. This function is not precisely the aforementioned equally that of native-born Americans: immigrants tend to work in different jobs with different skill levels. Yet, despite the size of the strange-built-in population, immigrants tend to accept relatively pocket-size impacts on the wages of native-built-in workers. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, immigrants generally accept positive impacts on both government finances and the innovation that leads to productivity growth.

Immigration policy is often hotly debated for a multifariousness of reasons that have piffling to do with a conscientious cess of the show. We at The Hamilton Project put frontward this fix of facts to help provide an evidence base for policy discussions that is derived from data and research.

Chapter 1. How Immigration Has Changed over Time

Fact 1: The foreign-built-in share of the U.Due south. population has returned to its late-19th-century level.

Immigrants take always been function of the American story, though clearing has waxed and waned over time. Immigration during the second one-half of the 19th century lifted the foreign-born share of the population to 14 per centum. Starting in the 1910s, however, clearing to the United States roughshod precipitously, and the foreign-born share of the population reached a celebrated low of 4.7 percentage in 1970.

This drib occurred in large part because of policy changes that limited immigration into the United states of america. Beginning with tardily-19th-century and early on-20th-century policies that were directed against immigrants from detail countries—for example, the Chinese Exclusion Deed of 1882—the federal government then implemented comprehensive national origin quotas and other restrictions, reducing total immigration inflows from more than 1 meg immigrants annually in the late 1910s to only 165,000 by 1924 (Abramitzky and Boustan 2017; Martin 2010). Economic turmoil during the Great Depression and two world wars also contributed to declining immigration and a lower strange-born fraction through the heart of the 20th century (Blau and Mackie 2017).

In the second half of the 20th century, a series of immigration reforms—including the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Deed—repealed national origin quotas and implemented family reunification and skilled immigration policies. In 1986 amnesty was provided to many people who were living in the United States without documentation (Clark, Hatton, and Williamson 2007). Unauthorized clearing was estimated at about 500,000 in the early 2000s, simply has since dropped sharply to a roughly nothing net inflow (Blau and Mackie 2017).

The strange-born fraction of the population rose steadily from 1970 to its 2017 level of xiii.7 percent. From 2001–14, legal clearing rose to roughly i 1000000 per year, marking a return to the level of the early on 20th century, but now representing a much smaller share of the total U.South. population. Today, at that place is a broad variation of the foreign-born population across states, ranging from nether five per centum in parts of the Southeast and Midwest to over 20 percentage in California, Florida, New Jersey, and New York (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 2017; authors' calculations).

Fact 2: The rising strange-born share is driven past both immigration flows and depression fertility of native-born individuals.

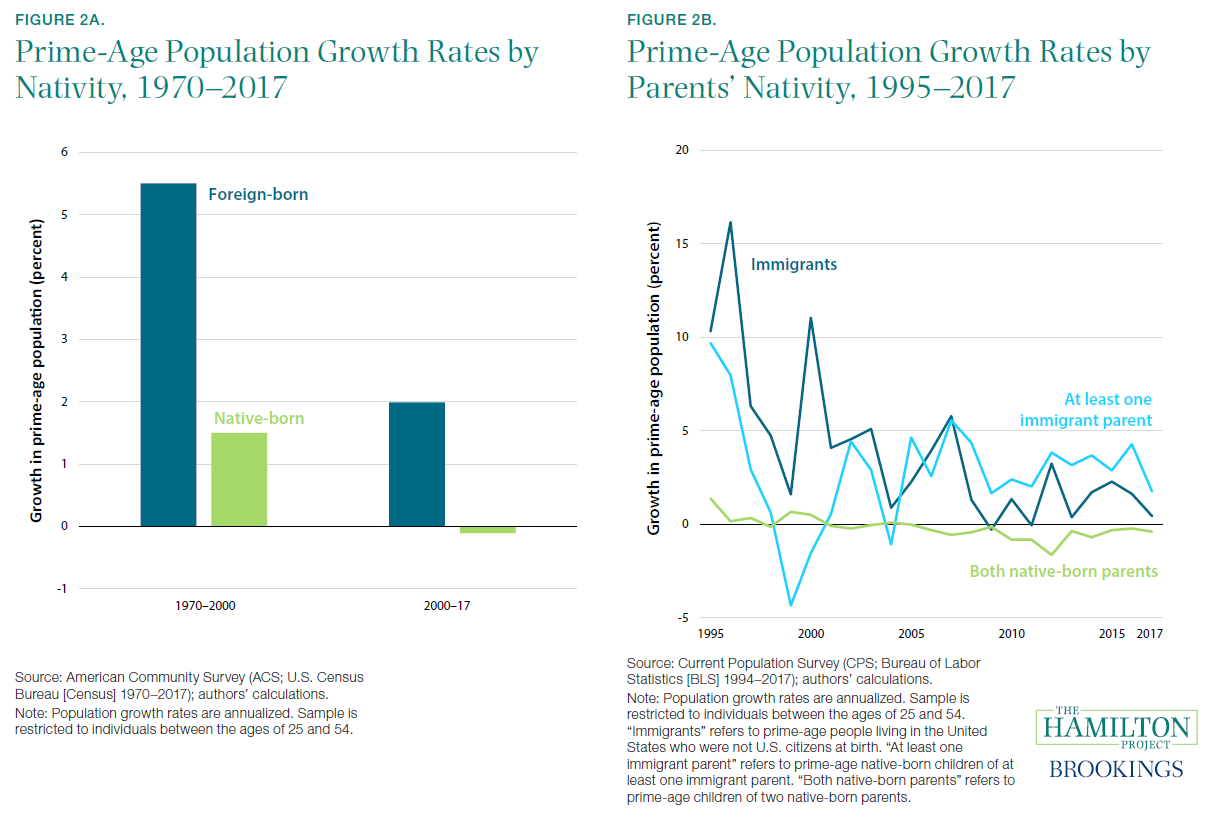

Though the strange-born fraction has risen to its late-19th-century levels, the net migration rate is just one-half the level that prevailed around 1900 (Blau and Mackie 2017). With declining native-born population growth in recent years, even a macerated level of cyberspace migration has been enough to raise the foreign-born fraction (see figure 2a).

Figure 2b shows that recent growth in the number of prime number-age children of immigrants has continued at more than iii percentage, supporting overall U.S. population growth. Past dissimilarity, the population growth charge per unit of prime number-age children of native parents has fallen from an average of 0.2 percent over the 1995–2005 period to an average of –0.five percent over the 2006–17 menses. The population growth of start-generation immigrants remains relatively high—1.eight percent on average from 2006 to 2017—but has fallen equally net migration has slowed. Thus, the continued rise of the foreign-born share of the population since 1990 does not reflect a surge in immigration just rather a slowing migration charge per unit combined with slowing growth in the population of children of natives.

From 1960 to 2016 the U.S. total fertility rate fell from 3.65 to ane.fourscore (World Bank n.d.). Demographers and economists believe that this reject was driven by a collection of factors, including enhanced access to contraceptive technology, irresolute norms, and the rising opportunity cost of raising children (Bailey 2010). Equally women's labor market place opportunities amend, child-rearing becomes relatively more expensive. Feyrer, Sacerdote, and Stern (2008) note that in countries where women have outside options only men share little of the child-care responsibilities, fertility has fallen even more.

Population growth is of import for both fiscal stability and robust economic growth. Social Security and Medicare become more difficult to fund equally the working-age population declines relative to the elderly population. (See fact 11 for a broader discussion of immigrants' fiscal impacts.) Moreover, overall economic growth depends to an of import extent on a growing labor strength (see fact 8).

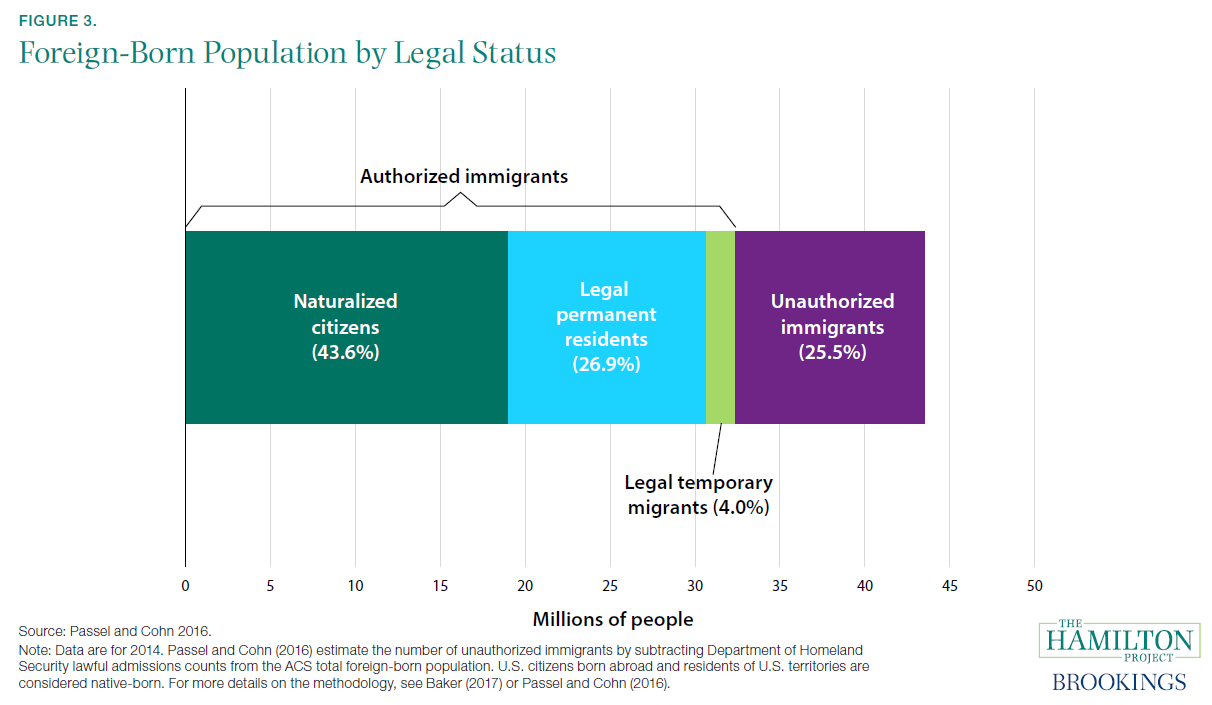

Fact three: Virtually three-quarters of the foreign-built-in population are naturalized citizens or authorized residents.

There are many ways in which immigrants come to the Usa and participate in this country's economical and social life. As of 2014 many in the foreign-born population had achieved U.South. citizenship (43.6 percent), while others had legal permanent resident status (26.9 percent), and withal others were temporary residents with authorization to alive in the country (4.0 per centum). The remaining 25.5 percent of foreign-built-in residents are estimated to be unauthorized immigrants, equally shown in figure iii. This is down from an estimated 28 percent in 2009 (Passel and Cohn 2011).

Unauthorized immigrants are the focus of intense policy and research attention. Some characteristics of these immigrants may be surprising: for example, more than 75 percent of all unauthorized immigrants have lived in the Us for more 10 years. This marks a sharp increase from 2007, when an estimated 44.5 percent were at least ten-year residents. Moreover, only eighteen.nine percentage of unauthorized immigrants are estimated to be 24 or younger, and 75.1 percent are in the prime working-age (25–54) group (Baker 2017).

There has also been special policy attention paid to those who entered the United States every bit children, including the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy introduced in 2012 to let temporary fractional legal status to those who came to the United States every bit children, who are now fifteen–31 years erstwhile, who accept committed no crimes, and who have been in the United states of america continuously since 2007. Roughly 800,000 people have used the program and estimates suggest 1.3 million were eligible (nigh 10 pct of the undocumented population) (Robertson 2018). Other proposed legislation—the American Promise Act—could touch as many as three.5 meg people (a third of the undocumented population) (Batalova et al. 2017).

The terms of immigrants' residency are important for their labor market outcomes, and potentially for the impacts they have on native-born workers. Without authorized status and documentation, foreign-built-in residents likely have little bargaining power in the workforce and are exposed to a higher gamble of mistreatment (Shierholz 2018).

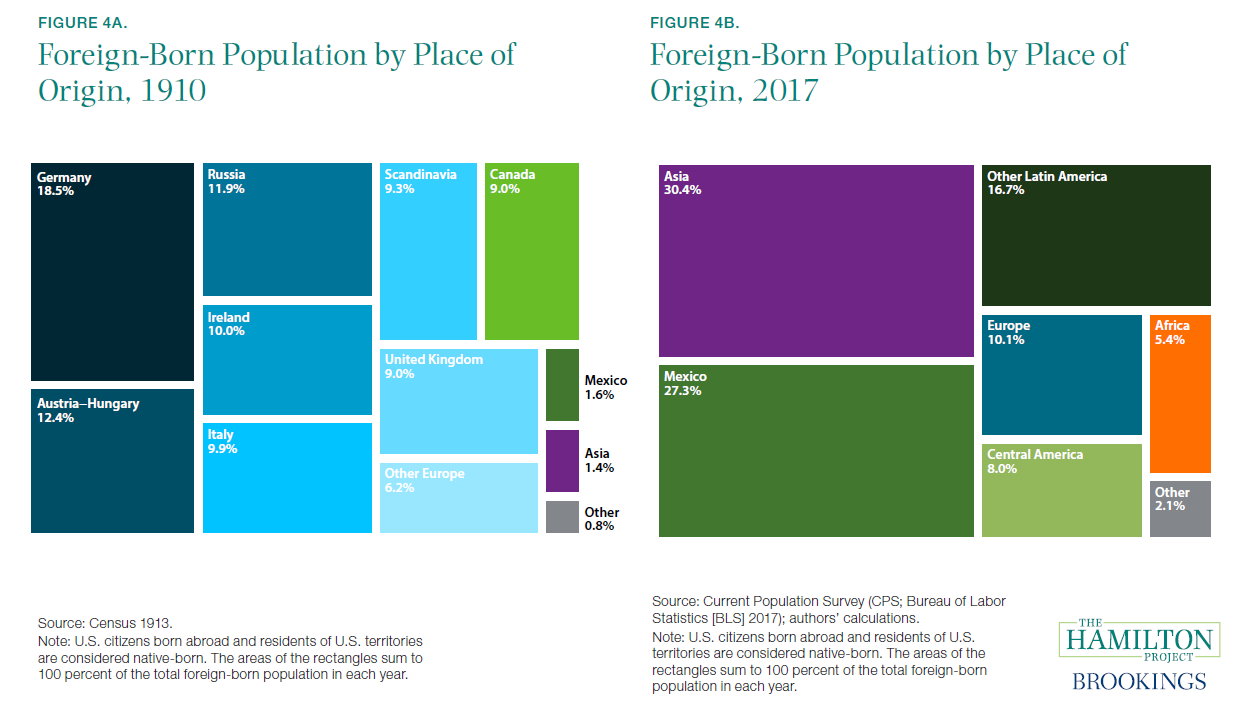

Fact 4: fourscore percent of immigrants today come from Asia or Latin America, while in 1910 more than 80 percent of immigrants came from Europe.

The countries of origin of immigrants to the United States have changed dramatically over the past century. Figure 4a shows that in the early 20th century the overwhelming majority of migrants entering the United States came from Europe. (The areas of the rectangles sum to 100 percent of the total foreign-born population in each year.) Although immigrants were predominantly from Western Europe, significant numbers arrived from Eastern Europe and Scandinavia as well. Today, the makeup of U.S. immigrants is much different: most 60 percent of the strange-built-in emigrated either from Mexico (which accounted for only i.half-dozen percent of the foreign-built-in in 1910) or Asian countries (which accounted for only 1.four percent in 1910).

India and China at present account for the largest share (6.5 and 4.vii percent of all immigrants, respectively) amid Asian immigrants, while El Salvador (three.iv percent) and Cuba (2.9 pct) are the primary origin countries in Latin America (later on United mexican states). As of 2017 immigrants from Federal republic of germany account for the largest share of European immigrants (only 1.one percent of all immigrants).

While the countries of origin may be different, there is some similarity in the economical situations of the origin countries in 1910 and today. GDP per capita of Republic of ireland and Italy in 1913 were 45.4 and 33.7 percent, respectively, of U.S. per capita income in 1913, simply today Western European GDP per capita is much closer to the U.S. level.[2] In 2016 Mexico's per capita income was 29.8 percent of per capita income in the Us (Bolt et al. 2018). Then as now large numbers of immigrants were drawn to relatively strong economic opportunities in the The states (Clark, Hatton, and Williamson 2007).

Chapter 2. The Education, Occupations, and Employment of U.S. Immigrants

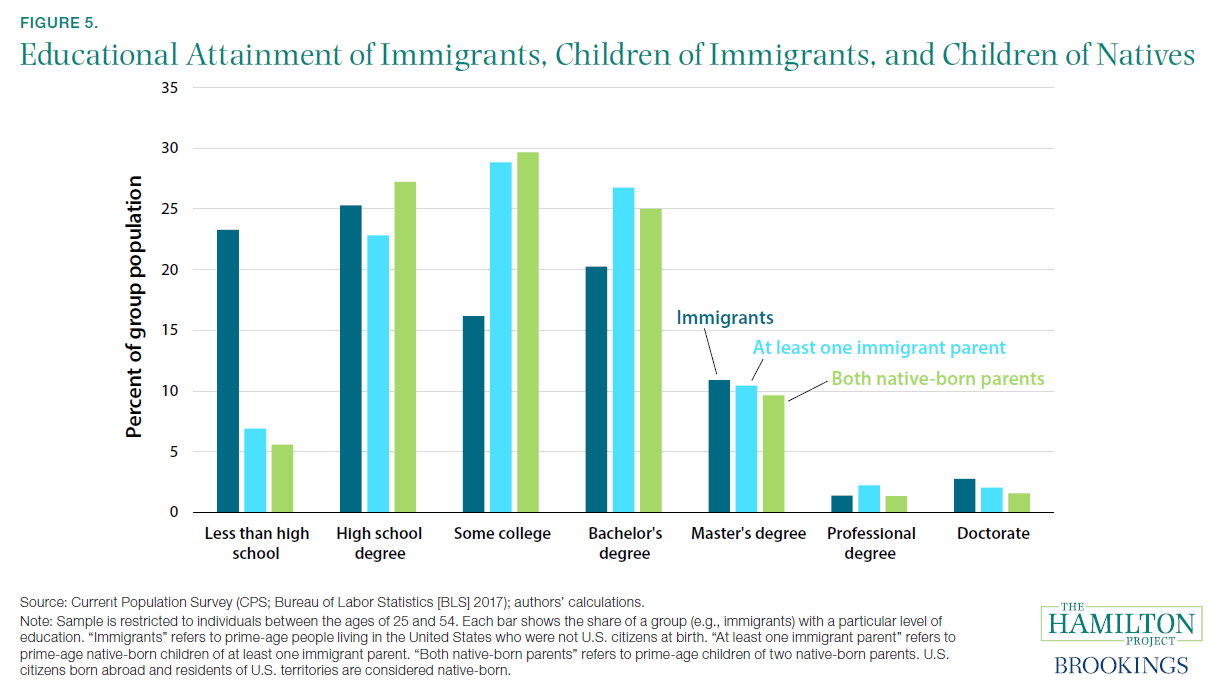

Fact v: Immigrants are 4 times more likely than children of native-born parents to take less than a loftier school degree, but are almost twice as likely to have a doctorate.

The educational attainment of immigrants is much more than variable than that of native-born individuals: there are more than immigrants with less than a high school degree, but also more immigrants with a master's caste or doctorate (relative to children of native-born parents), as shown in figure five. This reflects the diversity of background that characterizes immigrants. Of all prime number-age foreign-born persons in the U.s.a. with a postsecondary degree, 58.0 percentage are from Asian countries, while 51.two percent of all prime-age foreign-born persons with a high schoolhouse degree or less are from Mexico (BLS 2017; authors' calculations).

Immigrants to the United States are probable more positively selected on instruction and prospects for labor marketplace success relative to nonimmigrants (Abramitzky and Boustan 2017; Chiswick 1999). This selection may take increased since 2000, with disproportionate growth in the highly educated strange-built-in population (Peri 2017). A few features of the U.s.a. contribute to this tendency: first, the relatively limited social safe net available to immigrants makes the Usa a less attractive destination for those with poor labor market prospects. Second, the U.s. is characterized past more wage inequality than many culling destinations, with college rewards available for high-skilled than for low-skilled workers. Third, the high cost of migration (due in large part to the physical distance separating the United States from virtually countries of origin) discourages many would-be immigrants who do not look large labor market returns (Borjas 1999; Clark, Hatton, and Williamson 2007; Fix and Passel 2002).

Regardless of the characteristics of their parents, children of immigrants tend to reach educational outcomes that are like those of natives, but with higher rates of higher and postgraduate attainment than observed for children of natives (Chiswick and DebBurman 2004).[3] For example, figure 5 shows that children of immigrants receive all degrees at roughly the charge per unit of children of native parents, though the sometime take a slightly higher propensity to take either less than a high school degree or an avant-garde degree.

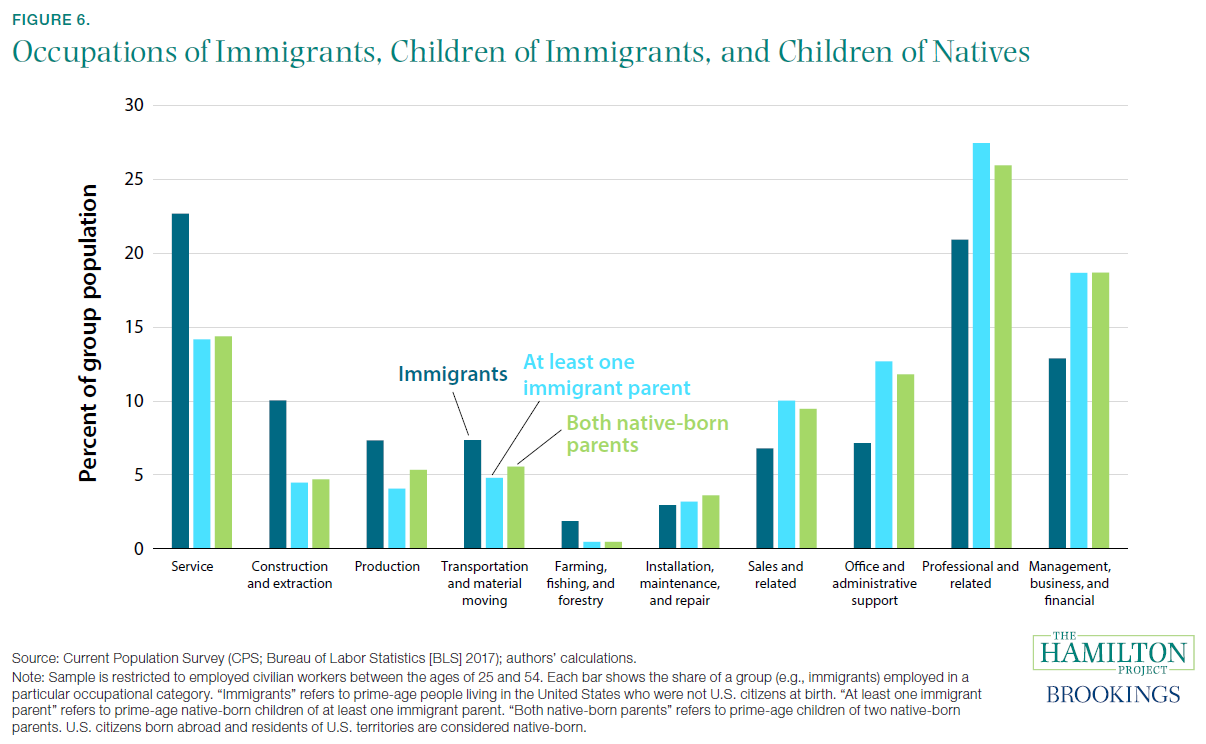

Fact 6: Immigrants are much more likely than others to work in structure or service occupations, but children of immigrants work in roughly the same occupations as the children of natives.

Differences in educational outcomes for foreign-born and native-built-in Americans are accompanied by occupational differences. The nighttime bluish and light dark-green bars in effigy half dozen testify the fraction of immigrant workers and children of native-born workers, respectively, in a given occupational group. Immigrant workers are 39 pct less likely to work in office and administrative support positions and 31 per centum less likely to work in management, while being 113 percent more likely to work in construction.

At the aforementioned fourth dimension, immigrant workers accounted for 39 per centum of the 1980–2010 increment in overall science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Stalk) employment, rising to 29 percent of STEM workers in 2010. By dissimilarity, loftier-skilled native-born workers tended to enter occupations that require more than communications and interpersonal skills (Jaimovich and Siu 2017). Amid high-skilled immigrants, caste of English proficiency predicts occupational option (Chiswick and Taengnoi 2008).

Some other bulwark to entry in some occupations consists of occupational licensing requirements, which can necessitate that immigrants appoint in costly duplication of training and experience (White House 2015).

The gaps shown in figure vi tend to diminish across generations. At that place are nigh no appreciable differences in occupations between the children of immigrants and children of natives.

The entrepreneurial behavior of foreign- and native-born individuals as well appears to be similar. While immigrants are more probable to be self-employed, they are not more probable to kickoff businesses with substantial employment: immigrant workers at each education level are roughly every bit likely as native-born people to ain businesses that employ at least 10 workers (BLS 2017; authors' calculations).

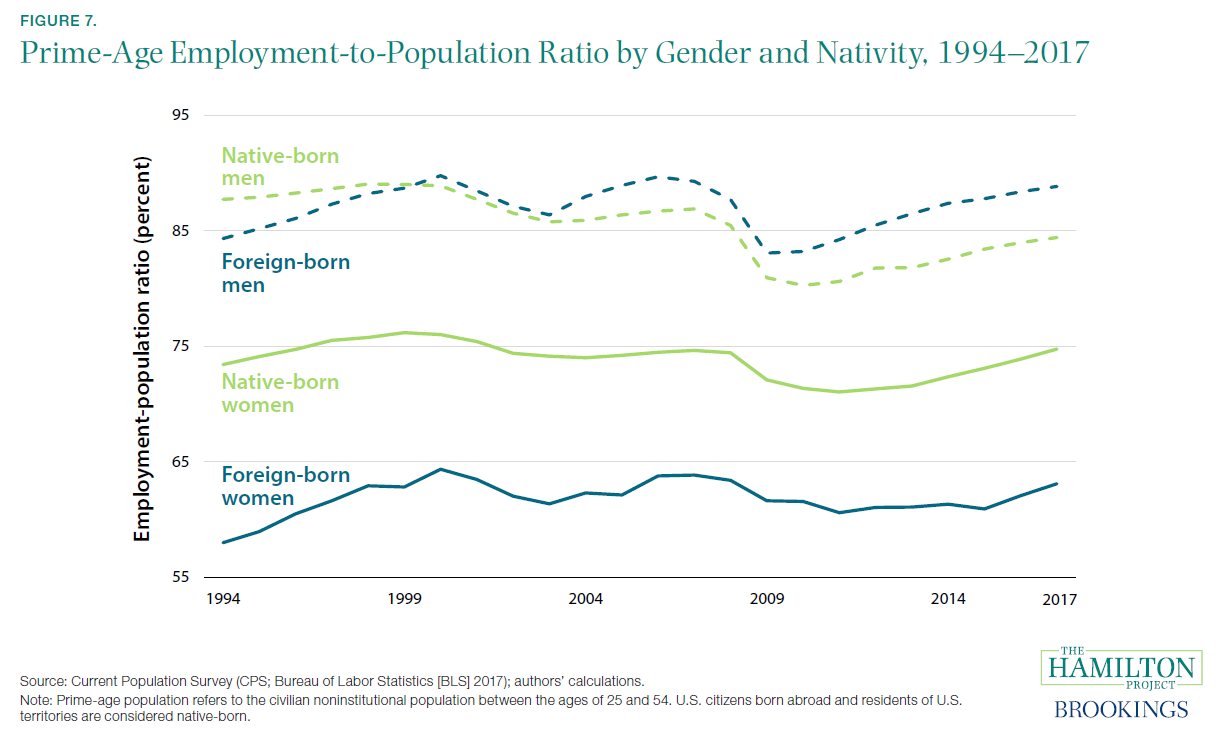

Fact 7: Prime-age foreign-built-in men work at a higher rate than native-built-in men, but foreign-born women piece of work at a lower rate than native-born women.

Immigrants xvi and older work at a higher charge per unit than native-born individuals (BLS 2017; authors' calculations), but this belies sharp differences by age and gender, and we therefore focus on prime-age men and women separately. In 2017 foreign-born prime-historic period (25–54) men worked at a rate 3.four per centum points higher than native-born prime-age men, while strange-born prime-age women worked at a rate 11.iv per centum points lower than native-born prime-age women. For undocumented immigrants, this divergence betwixt male person and female employment is even more pronounced (Borjas 2017).

Women—whether foreign- or native-born—face large economic, policy, and cultural obstacles to employment (Blackness, Schanzenbach, and Breitwieser 2017). These obstacles may exist larger for foreign-born women than for natives. Moreover, some immigrants come up from cultures where women are less likely to work exterior the abode (Antecol 2000).

Figure 7 shows how foreign- and native-born employment rates take evolved over the past 20 years. The relatively stable levels of foreign-born employment reverberate the offsetting forces of rising labor strength participation for a given accomplice as it spends more fourth dimension in the The states too equally the arrival of new cohorts of immigrants. For both men and women immigrants, hours worked and wages tend to better apace upon entry to the The states (Blau et al. 2003; Lubotsky 2007).

Employment rates for depression-skilled foreign-built-in individuals are considerably higher than those of natives. For example, 72.eight per centum of strange-born prime number-age adults with a high school degree or less are employed (men and women combined), as compared to 69.5 percent for their native-born counterparts. The gap is much larger for those without a high schoolhouse educational activity: lxx.3 percent of the foreign-born are employed and only 53.i per centum of the native-born are employed (BLS 2017; authors' calculations).

Chapter iii. The Effects of Immigrants on the U.S. Economy

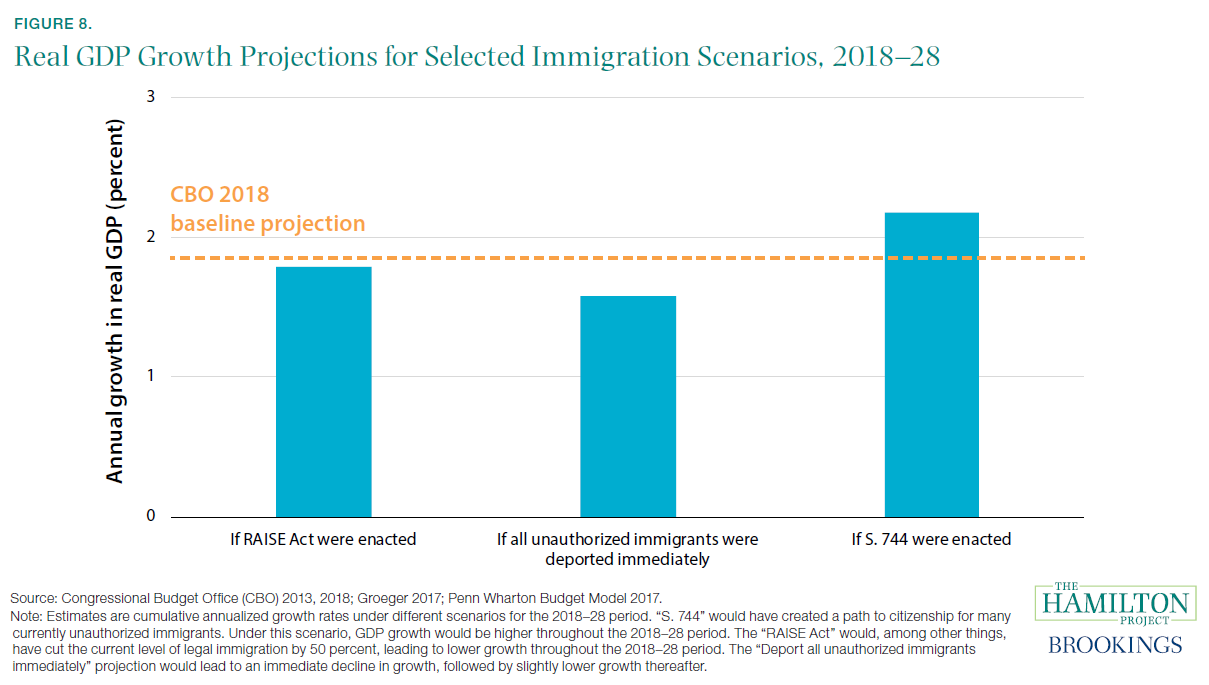

Fact 8: Output in the economy is higher and grows faster with more than immigrants.

At that place is wide agreement among researchers and analysts that immigration raises total economic output (Borjas 2013; Congressional Budget Part [CBO] 2013). Past increasing the number of workers in the labor strength, immigrants enhance the productive capacity of the U.S. economy. One gauge suggests that the total annual contribution of strange-born workers is roughly $2 trillion, or about ten per centum of annual Gross domestic product (Blau and Mackie 2017 citing Borjas 2013); the contribution of unauthorized immigrants is estimated to be almost 2.six per centum of Gross domestic product (Edwards and Ortega 2016; authors' calculations). As shown in figure 8, providing documented status to many current unauthorized immigrants (which should increment their productivity past allowing better task matching) and allowing more than immigration would increase annual Gdp growth past 0.33 per centum points over the next decade, while removing all current unauthorized immigrants would lower annual GDP growth by 0.27 percentage points during that same period (CBO 2013, 2018; Penn Wharton Budget Model 2017).

The economic effects of new workers are likely different over the short and long run. In the short run, a large increase or decrease in the number of immigrants would probable cause disruption: an increment could overwhelm bachelor infrastructure or possibly put downwardly pressure level on wages for native-born workers until majuscule accumulation or engineering usage can adjust (Borjas 2013), while a subtract could harm businesses with fixed staffing needs, or lead to underutilization of housing and other similar capital (Saiz 2007; White House 2013).

Immigrants and natives are not perfectly interchangeable in terms of their economic furnishings: immigrants bring a somewhat different mix of skills to the labor market than exercise native workers, as detailed previously in this document. High-skilled immigration is peculiarly likely to increase innovation (see fact 10). In add-on to these supply-side effects, immigrants also generate demand for goods and services that contribute to economic growth.

However, these positive impacts on innovation and growth exercise not necessarily mean that additional immigration raises per capita income in the United States (Friedberg and Hunt 1995). For case, if immigrant workers were on boilerplate less productive than native-born workers, additional immigration would reduce per capita Gross domestic product while increasing total economic output. Similarly, immigration may or may not lead to improved outcomes for native workers and for U.S. authorities finances; we talk over both concerns in subsequent facts. Most estimates propose that immigration has a pocket-sized positive impact on Gdp over and in a higher place the income of immigrants themselves (Blau and Mackie 2017; Borjas 2013).

Fact nine: Most estimates testify a modest impact of immigration on depression-skilled native-born wages.

It is uncontroversial that immigrants increase both the labor forcefulness and economic output. However, it is less obvious whether immigrants might lower wages for some native-born workers (Friedberg and Hunt 1995). In detail, low-wage native-born workers might be expected to suffer from the increased labor supply of low-skilled competitors from away, given that many immigrants tend to have lower skills than the overall native population (see effigy five).

Other adjustments could mute this touch. Firms could rearrange their operations to accommodate more than workers and produce proportionally greater output, particularly over the long run (Friedberg and Hunt 1995). Firms announced to adapt technology and capital based on immigration and the skill mix of the local population (Lewis 2011). Foreign-born and native-built-in workers may be imperfect substitutes, fifty-fifty when they possess similar educational backgrounds (Ottaviano and Peri 2012).

In addition, the impact of low-skilled immigrants may be diluted (i.e., shared across the entire national labor market place) every bit native workers and firms respond by rearranging themselves beyond the rest of the country (Bill of fare 1990). Strange-born workers announced to be especially responsive to economic shocks every bit they search for employment: Mexican low-skilled men are more than apt to motility toward places with improving labor market prospects (Cadena and Kovak 2016). Finally, immigrants—depression-skilled or high-skilled—contribute to labor need too every bit labor supply to the extent that they consume goods and services in addition to condign entrepreneurs (White House 2013).

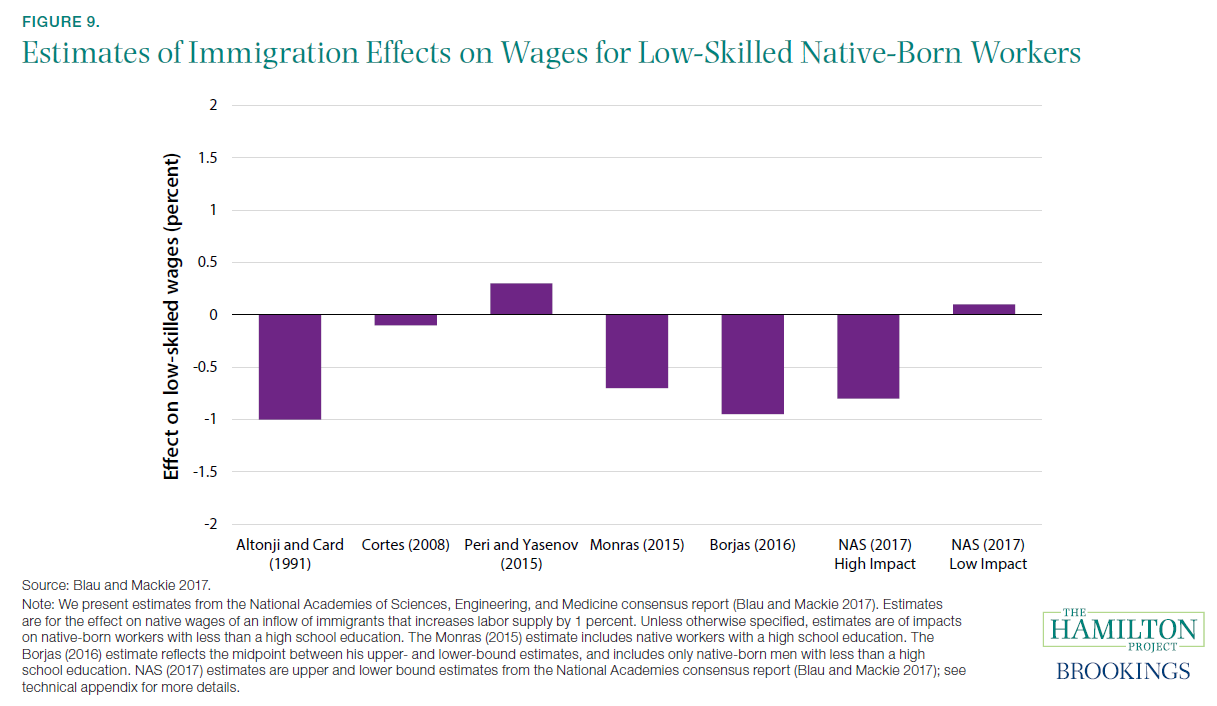

Information technology is therefore an empirical question whether low-skilled immigration actually depresses wages for low-skilled natives. The consensus of the empirical literature is that this does not occur to any substantial extent (see figure 9, which presents estimates used in the National Academies of Sciences, Technology, and Medicine consensus report). Nearly estimates in figure 9 prove an impact on low-skilled native-born wages of 0 percent to –1 percent. Another recent estimate of the bear upon on low-skilled natives (Ottaviano and Peri 2012) estimated a slightly positive impact on wages (betwixt 0.half dozen and one.seven pct). Furthermore, the impacts on wages of native-born workers with more than didactics are by and large estimated to be positive, such that most estimates observe the overall bear on on native workers is positive (Blau and Mackie 2017; Kerr and Kerr 2011; Ottaviano and Peri 2012).

Fact 10: Loftier-skilled immigration increases innovation.

Every bit discussed in fact 6, the kind of work that immigrants practice is often different than that of native-born workers. In particular, immigrants are more than likely to possess college and avant-garde degrees, and more probable to piece of work in Stalk fields. This in turn leads to disproportionate immigrant contributions to innovation.

One useful proxy for innovation is the acquisition of patents. Immigrants to the U.s. tend to generate more patentable technologies than natives: though they institute only xviii percentage of the 25 and older workforce, immigrants obtain 28 per centum of high-quality patents (divers as those granted by all three major patent offices). Immigrants are likewise more likely to become Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry, and physiology or medicine (Shambaugh, Nunn, and Portman 2017).

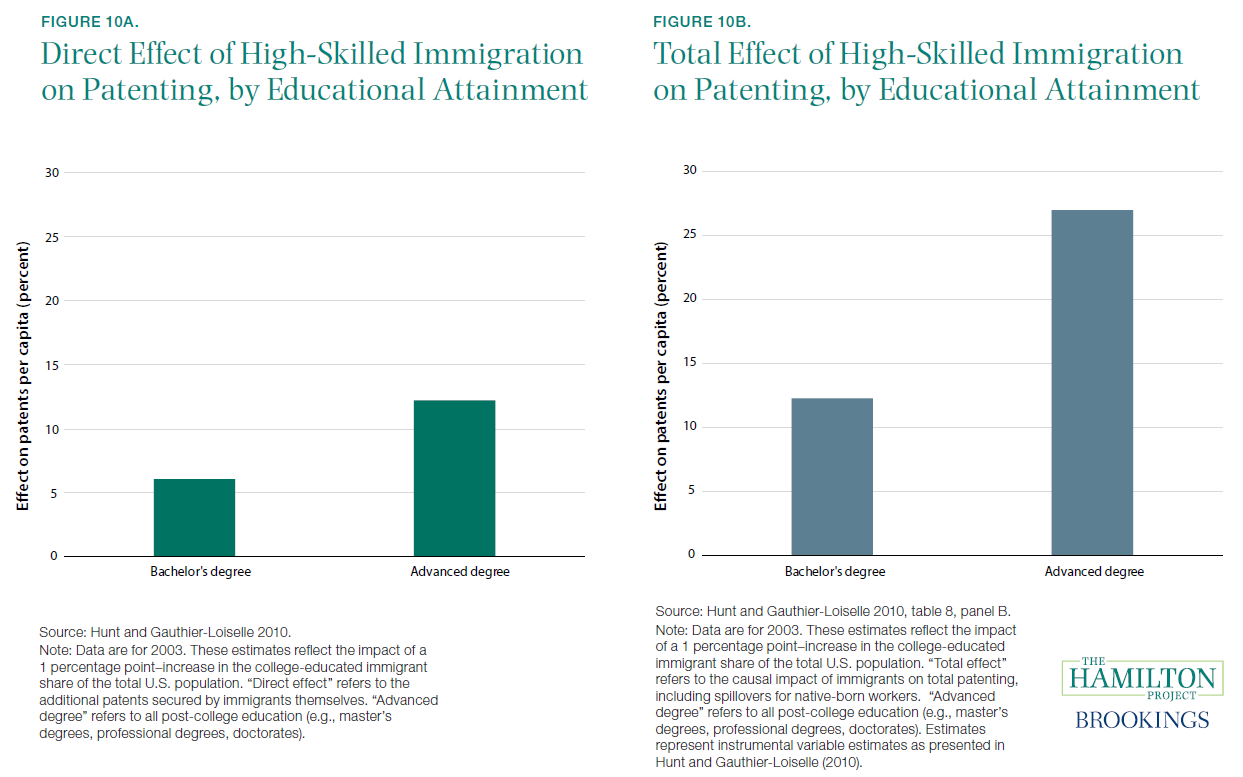

Presenting estimates from Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010), figure 10a shows the direct impact of high-skilled immigrants on patenting per capita based on their higher propensity to patent. Increasing the share of college-educated immigrants in the population by i percentage point increases patents per capita by 6 percent. This affect is roughly twice as large for those with advanced degrees.

Effigy 10b shows the total impact—which includes both the directly impact as well as whatever spillovers to the productivity of native-born workers—of an increase in the high-skilled immigrant share of the population. Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle observe that spillovers are substantial and positive. A one percentage indicate–increase in the college-educated or avant-garde degree-property immigrant shares of the U.S. population are estimated to produce a 12.3 percent or 27.0 percent increase in patenting per capita, respectively.

In an examination of foreign-born graduate students, Chellaraj, Maskus, and Mattoo (2008) also find positive spillovers for native-built-in innovation. Research examining short-run fluctuations in the number of H-1B visas similarly concludes that immigrants add together to aggregate innovation, although estimates of spillovers for innovative activities of native-born workers are smaller or nonexistent (Kerr and Lincoln 2010).

Fact 11: Immigrants contribute positively to authorities finances over the long run, and high-skilled immigrants make especially big contributions.

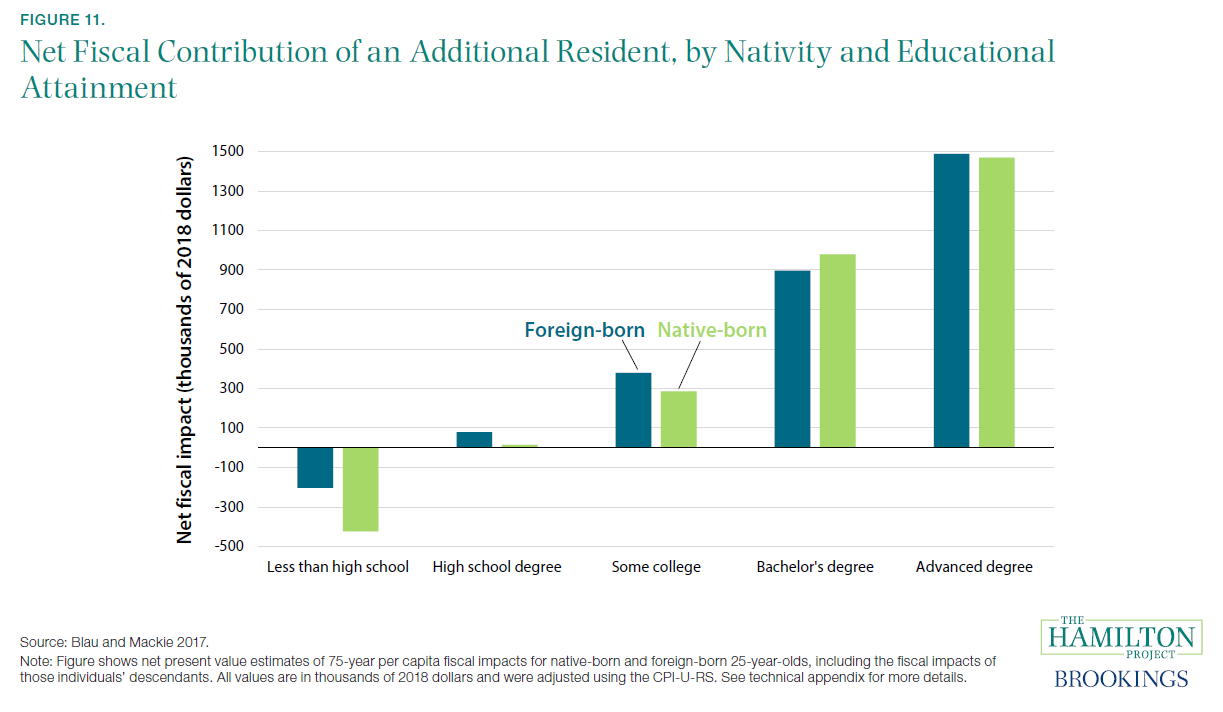

With its complicated system of taxes and transfers, the United States is afflicted in a diversity of different ways by the arrival of immigrants. Figure eleven provides estimates of immigrants' fiscal impacts (including the fiscal impacts of their descendants), shown separately past level of educational attainment. These estimates include direct spending on individuals through the social safety internet or other programs too equally taxes paid. The estimates practise not include public expenditures on categories similar public safety, national defense force, and interest on the debt, considering these expenses do not necessarily increment as the population rises. If those expenses were included, the fiscal bear upon of each category of foreign-built-in and native-born workers would be more negative, just the overall pattern would remain the aforementioned.

Workers with more instruction and higher salaries tend to pay more taxes relative to their apply of government programs, and that is reflected in the more-positive fiscal impacts of highskilled individuals. Looking separately at acquirement and outlay implications, almost of the variation in immigrant financial affect across instruction levels is due to differences in the amount of taxes paid (Blau and Mackie 2017, 444–60). Moreover, recent immigrants have tended to experience improve labor market place outcomes than the overall immigrant population; in part this is due to the more-recent arrivals being better educated, which leads to them having an even more than-positive fiscal impact (Orrenius 2017).

Across the educational categories, the foreign-born population is estimated to have a slightly more-positive financial impact in nearly every category. For the strange-born population equally a whole, per capita expenditure on greenbacks welfare help, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Plan (SNAP; formerly known as the Food Stamp Program), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security are all lower than for native-born individuals, even when restricting the comparison to age- and income-eligible individuals (Nowrasteh and Orr 2018).

Fact 12: Clearing in the Usa does not increment crime rates.

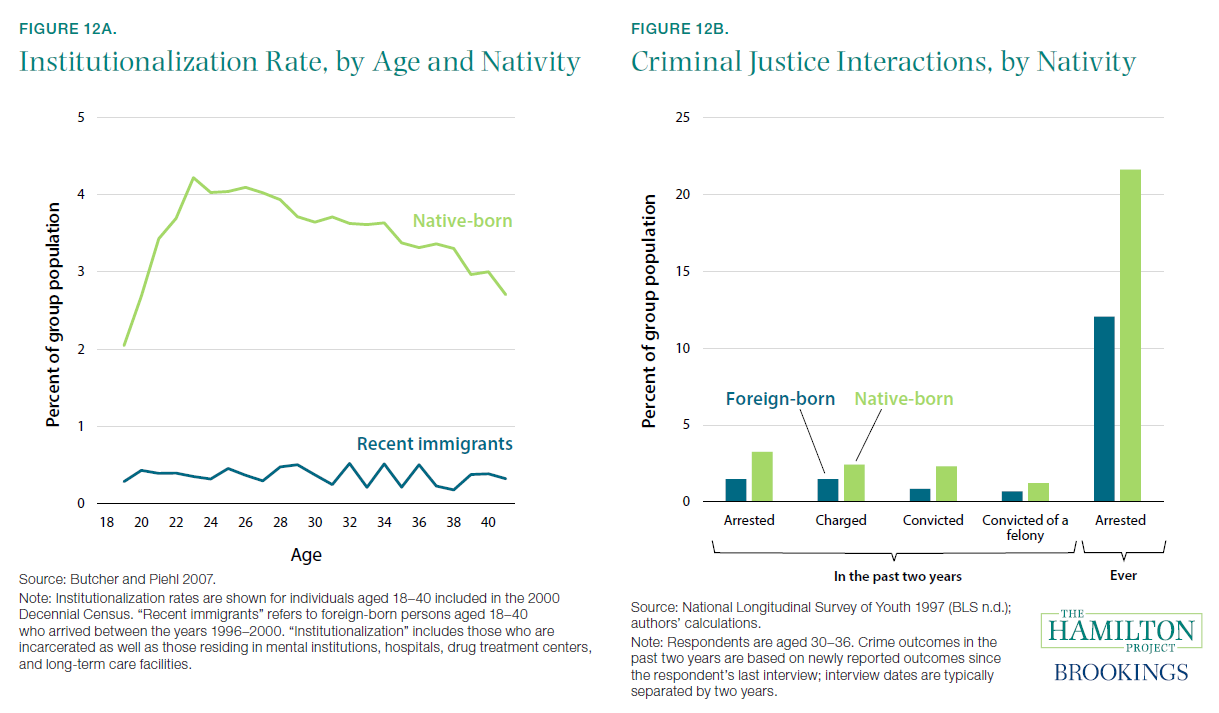

Immigrants to the United States are considerably less likely than natives to commit crimes or to exist incarcerated. As shown in figure 12a, recent immigrants are much less likely to be institutionalized (a proxy for incarceration that besides includes those in health-care institutions similar mental institutions, hospitals, and drug treatment centers) at every historic period.

Why practise immigrants accept fewer interactions with the criminal justice system? Immigrants are subject to diverse kinds of formal and informal screening. In other words, institutions and incentives often crusade the United States to receive migrants who are advantaged relative to their origin-state counterparts (Abramitzky and Boustan 2017) and less disposed to commit crimes. At the time of Butcher and Piehl's analysis, deportation was not a major factor; rather, self-choice of depression-law-breaking-propensity immigrants into the United States appears to have been the driver (Butcher and Piehl 2007).[iv]

There is an important caveat to this account: contempo immigrants have had less time to be arrested and imprisoned in the U.s. than have natives. In other words, there may be a somewhat smaller gap in their criminal action versus natives, but the U.S. criminal justice system has had less time to detain and incarcerate them (Butcher and Piehl 2007). Figure 12b therefore looks more specifically at the criminal justice interactions of native-born and foreign-born adults over a narrower window of time. It shows that xxx- to 36-year-old immigrants are less likely to have been recently arrested, incarcerated, charged, or convicted of a criminal offence when compared to natives, confirming the broader pattern of figure 12a. Research examining quasi-random variation in Mexican immigration has also establish no causal impact on U.S. criminal offense rates (Chalfin 2014).

In addition to the broader question of how immigrants as a group affect crime and incarceration rates, it is important to understand how changes in the legal condition of immigrants can affect criminal justice outcomes. Show suggests that providing legal resident status to unauthorized immigrants causes a reduction in crime (Baker 2015). This is associated with improvements in immigrants' employment opportunities and a corresponding increase in the opportunity cost of criminal offence. Conversely, restricting access to legal employment for unauthorized immigrants leads to an increased crime rate, particularly for offenses that help to generate income (Freedman, Owens, and Bohn 2018). In full, unauthorized immigration does not seem to have a meaning event on rates of violent crime (Green 2016; Light and Miller 2018).

[1] We use the terms "immigrants" and "strange-born" to refer to people living in the United States who were non U.S. citizens at birth. We refer to the native persons of at least ane immigrant parent—whether built-in in the U.South. or abroad—with the term "second generation" or "children of immigrants". We refer to native persons of two native parents, persons built-in away of two native parents, and persons born in a U.S. territory of two native-born parents with the term "children of natives."

[2] Data is used for 1913 instead of 1910 considering Bolt et al. (2018) does non include information for Ireland in 1910. The closest twelvemonth for which the dataset had GDP per capita for the Usa, Italian republic, and Republic of ireland was 1913.

[3] Results are not sensitive to whether we consider children of exactly one immigrant parent to be children of immigrant parents or children of native-built-in parents.

[iv] The intensity and form of detention and deportation actions has changed essentially over the past few years and requires further inquiry.

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-dozen-facts-about-immigration/

0 Response to "What Is Just Facts About Immigration Review of Website"

Post a Comment